This report on the state of the Church of England is of interest to all who love the truth of God, irrespective of our view of that particular religious body.

The ‘Church of England’ emerged from the mists of religious and political controversy in the 16th century, trailing with it much of the ways, the language, the costumes and the errors of popish trumpery!

There were many very brave men and women who did their best to further reform the new ecclesiastical body, many of whom paid with their lives their faithfulness to God and His Word.

In the seventeenth century, under Charles II, the ‘Church’ was purged of virtually all who desired a greater reforming and a closer alignment in faith and practice with the Word of God. They were literally cast out into the street at the King’s command in what became known last the ‘Great Ejection’.

The ‘Act of Uniformity’ of Charles II prescribed that any minister who refused to conform to the 1662 Book of Common Prayer by St Bartholomew’s Day (24 August) 1662 should be ejected from the Church of England. This date became known as “Black Bartholomew’s Day” among Dissenters, a reference to the fact that it occurred on the same day as the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572.

Oliver Heywood estimated the number of ministers ejected at 2,500. This group included Richard Baxter, Edmund Calamy the Elder, Simeon Ashe, Thomas Case, John Flavel, William Jenkyn, Joseph Caryl, Benjamin Needler, Thomas Brooks, Thomas Manton, William Sclater, Thomas Doolittle, and Thomas Watson. Biographical details of ejected ministers and their fates were later collected by the historian Edmund Calamy, grandson of Calamy the elder.

In many ways, this was a mortal blow for the Church of England has ever since been an avenue by which false teaching and heresy has been introduced in ‘the name of the Lord’ and corrupt practices have been sanctioned by it.

It has been slowly dying as an institution ever since. This article gives further evidence of the corrupting process known as DEATH, being at an advanced stage in its ranks!

Naturally, the information given in this news report is the view of someone most likely ignorant of pure gospel truth. Nevertheless, as the mouth of that false prophet Balaam uttered that great truth which indicated his awareness of his great need of God’s mercy — “Who can count the dust of Jacob, and the number of the fourth part of Israel? Let me die the death of the righteous, and let my last end be like his!” Numbers 23:10, even so, in this article, truth regarding the moral state of the Church of England is to be found.

For any interested, here in pdf format is another article from ’The Times’ on the same theme about which I issue the same precautions!

The Times view on the Church of England: Behind the Times

Sincerely in Christ’s name,

Ivan Foster

Shifting attitudes of frontline clergy revealed in landmark poll

‘The Times’ — August 14 2023.

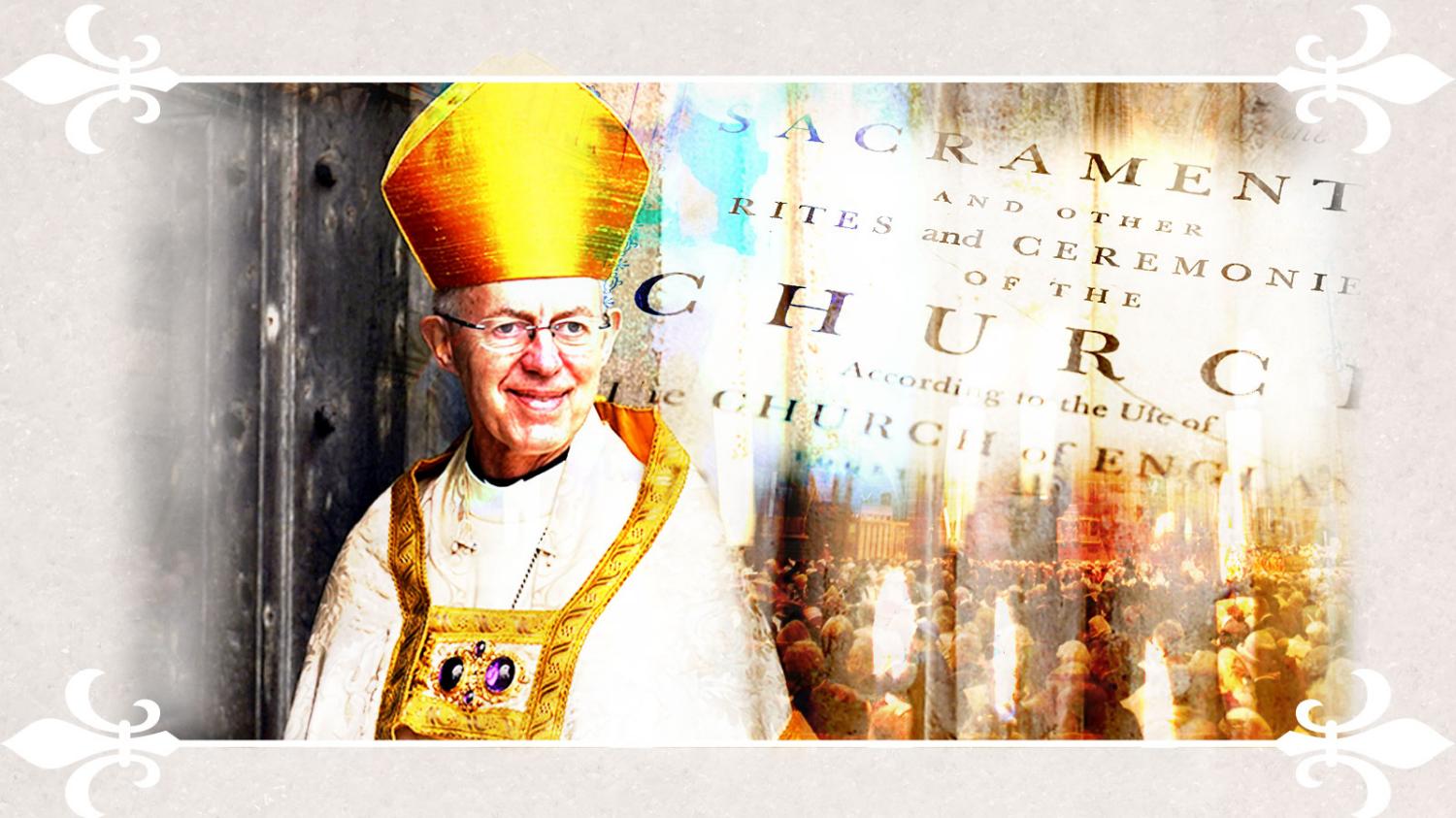

Justin Welby is the 105th Archbishop of Canterbury. The appointment of a woman to the position would be backed by more than 80 per cent of priests

Britain can no longer be described as a Christian country, three quarters of Church of England priests believe, according to a landmark survey conducted by The Times.

The most wide-ranging poll carried out among frontline Anglican clergy, and the first survey of Church of England clerics conducted in almost a decade, has found a strong desire among rank-and-file priests for significant changes in church doctrine on issues such as sex, sexuality, marriage and the role of women to bring it into greater line with public opinion.

A majority of priests want the church to start conducting same-sex weddings and drop its opposition to premarital and gay sex, in results described as “absolutely huge” by campaigners.

The survey also uncovered high levels of stress among priests, many of whom feel over-stretched. They fear that the church’s efforts to arrest the decline in attendance will fail and this may ultimately lead to its “extinction”.

The survey analysed responses from 1,200 serving priests, the catch-all term for all ordained people who can celebrate sacraments such as Holy Communion. The respondents mainly included vicars, rectors, curates, chaplains and retired priests who still serve, representing around 6 per cent of active clergy.

Asked whether they think “Britain can or cannot be described as a Christian country”, only a quarter (24.2 per cent) answered: “Yes, Britain can be described as a Christian country today”. Almost two thirds (64.2 per cent) said Britain can be called Christian “but only historically, not currently” while 9.2 per cent answered “no”.

Figures from the 2021 census showed that the proportion of people who identified as Christian in England and Wales had fallen below half for the first time — to 46.2 per cent — with the strongest growth among those who say they have “no religion”. The figure has trebled since 2001 to 37.5 per cent.

Asked why they felt under pressure, one priest cited the “pressure of justifying the Church of England’s position to increasingly secular and sceptical audiences”.

Professor Linda Woodhead, head of the department of theology and religious studies at King’s College London, said: “It’s extremely important to hear the clergy’s views. It’s hard to carry out these surveys which is why we have very few of them, and it is very interesting.”

She said the church had found itself in recent decades “pushed apart from public opinion on what’s right and wrong” on issues including sex and sexuality and said priests seemed to occupy a “middle ground” between traditional church teaching and broader public views.

Woodhead added: “This survey shows the clergy take a more moderate position than their leaders. [Frontline priests] are more in touch with their congregations and ordinary people. If they had been listened to more by leaders . . . the church might be in a better place today.”

The Times selected 5,000 priests at random from among those with English addresses in Crockford’s Clerical Directory of Anglican clergy and received 1,436 responses, analysing data from the 1,185 respondents still serving. No attempt has been made to survey Church of England priests nationwide since 2014.

It sought their views on topics from same-sex marriage in church, Brexit, migration policy, premarital sex and the race for net zero, to whether they would back a woman as Archbishop of Canterbury, how they would vote in a general election and what should be done with statues that commemorate slave traders.

In response to the survey, the Bishop of Leeds, the Right Rev Nick Baines, said on behalf of the church: “The church is the church, and, as such, not a club. It has a distinct vocation that does not include seeking popularity.”

He said: “Repentance means being open to changing our mind in order that society should encounter both love and justice. And this means sometimes going against the flow of popular culture, however uncomfortable that might be.”

He said the Times survey showed that priests were not “detached in an ivory tower, but really wrestling — thoughtfully and prayerfully — with the kinds of questions our society is also addressing”.

“Evidently, the Church hasn’t always got it right, but cannot escape the demands of its calling to be faithful to God in loving his world.”

The first tranche of results is set out below.

Historic shift on gay marriage and questions of sex

A majority of priests want the church to conduct same-sex weddings for the first time and formally drop its centuries-old opposition to premarital and gay sex, in a historic shift that campaigners hope will lead to a change in teaching.

The church teaches that only weddings between a man and a woman are permitted in church and that sex is only permissible within heterosexual marriages.

Bishops have, however, said they will allow priests to “bless” gay couples and are under pressure to go further and permit same-sex weddings. They are considering whether to drop the teaching that gay sex is “incompatible” with Christian teaching and whether to allow gay priests to have civil weddings, and will present their recommendations to the church’s assembly, the General Synod, this autumn.

The survey found majority support among priests for a change in law to allow priests to marry gay couples, with 53.4 per cent in favour versus 36.5 per cent against, suggesting that more than 10,600 of the church’s 20,000 priests would back it.

This is a reversal of the proportions the last time Anglican priests were asked about the broad issue in 2014, shortly after the legalisation of same-sex civil marriage, when 51 per cent declared same-sex marriage to be “wrong” compared with 39 per cent who said they backed it.

Woodhead conducted the 2014 survey and said: “It’s a very rapid change. These are very interesting findings. It’s fascinating that you’ve now got this change in attitudes.”

It has not been known how many priests would be willing to offer blessings to people in gay relationships if they were approved. The Times poll found that 59 per cent of priests would do so while 32.3 per cent will opt out.

The poll found that 62.6 per cent of priests thought the church should drop its opposition to premarital sex, with 21.6 per cent backing an end to the teaching and 41 per cent saying it should drop its opposition, but only for people in “committed relationships”. Just over a third (34.6 per cent) said the teaching should remain unchanged.

A resolution agreed by Anglican churches worldwide states that “homosexual practice is incompatible with scripture”. The Times poll found that 64.5 per cent of priests backed an end to this teaching, with 27.3 per cent backing an end to any requirement for celibacy for gay people and 37.2 per cent willing to accept sex between gay people in “committed” relationships such as civil partnerships or marriages. Almost a third (29.7 per cent) said the teaching should not change.

Bishops are also considering whether to lift the ban on gay priests entering civil marriages with their partners. The poll found 63.3 per cent of priests backed such a move, while 28.7 per cent opposed it.

The Rev Andrew Foreshew-Cain, who runs the Campaign for Equal Marriage in the Church, and married his partner in defiance of rules, said: “This is absolutely huge. I really think this [survey] is really important. It is really clear evidence of the direction of change the church needs to pursue. I hope this kind of evidence will enable the bishops to feel confidence that there is a wide majority for change.”

The Bishop of Oxford, the Right Rev Steven Croft, is one of the most prominent figures to back same-sex marriage, having changed his position from one of opposition. He said: “I think it’s really interesting. I think it’s very important that the question has been asked. I think it does show very much that the stance of clergy across the country is more in favour of change than the balance of views in the General Synod . . . I hope the synod will take notice of that as we move the proposals forward.”

The Rev Canon John Dunnett is director of the Church of England Evangelical Council, which has led protests against plans to offer blessings to same-sex couples. He said: “My overarching response is that it signposts a thoroughly divided Church of England. The question it raises, the million-dollar question, is how is the [church] is going to face a situation in which the level of division is both so substantial and runs so deep?”

He suggested that separate bishops, dioceses or provinces might be needed to cater to churches who oppose the recognition of same-sex relationships.

The change could affect many couples, including Abi Malthouse. For generations everyone in her family has got married in the same Norfolk church, but she was unable to wed her fiancée, Shelley, because she is a woman. The pair had to have a civil ceremony.

Malthouse said of the survey results: “I do feel encouraged that it’s possible that maybe people can either get married in a church for the first time or maybe renew their vows in a church. I’m really pleased and it’s a really positive thing that we have people within the [church] who have that opinion.”

An end to the rejection of women

The appointment of a woman as Archbishop of Canterbury would be backed by more than 80 per cent of priests, while two thirds want an end to the system that allows parishes to reject female leaders.

The Bishop of Dover, the Right Rev Rose Hudson-Wilkin, welcomed the results of the survey and said the church “cannot continue to speak with a forked tongue” by backing women in the priesthood, while also allowing parishes to reject them, warning that this would “destroy the ministry of women”.

She called for a review of measures that allow churches to turn down female applicants for vacant priest positions and reject the leadership of female bishops.

The survey asked priests: “Would you support or oppose the appointment of a woman as Archbishop of Canterbury?” Among the 1,179 who responded to the question, 80.2 per cent said they would support it versus 13.4 per cent who would oppose it.

The Most Rev Justin Welby is the 105th Archbishop of Canterbury, all of whom have been men. Only since 2014 have women been able to become bishops.

Welby does not reach the retirement age of 70 until January 2026 and so would not have to step down for more than two years. When he announces that he is leaving, a secretive committee called the Crown Nominations Commission would begin choosing a successor in a process that involves interviews, consultations and a period of “discernment” in which they try to ascertain God’s will.

Around a third of serving bishops are women, suggesting there is a wide field of possible female candidates for the role, including the Bishop of London, the third most senior cleric in the church, the Right Rev Sarah Mullally.

A total of 590 parishes, 4.8 per cent of the total, have formally declared that they will not accept a woman as their main priest or accept the oversight of a female bishop.

The system was introduced in 2014 after women won the right to become bishops. It was designed to support about 150 evangelical or “complementarian” parishes and about 440 Anglo-Catholic parishes that do not accept women in leadership roles.

Asked about the future of this system, a third of priests at 33.5 per cent said it should “remain in place indefinitely”, while 62.9 per cent said it should be “phased out” to prevent parishes from rejecting women.

Hudson-Wilkin said that she takes collective responsibility with other bishops to “do all I can” to make the present system work, but added: “The ministry of women in the church cannot be left permanently in a state of ‘reception’.

“To do so will be to ultimately destroy the ministry of women in the church as it will always be looked at with suspicion as well as being second class to that of the ministry of men. Enough time has passed for this whole matter to be reviewed.”

On the prospect of a woman in the church’s most senior clerical role, she said: “If a woman meets the qualification and has the essential criteria for becoming an archbishop, then there is no reason why the discernment process should not reflect this.”

The Bishop of Ebbsfleet, the Right Rev Rob Munro, represents evangelical parishes that do not accept women as leaders. He said the church had designed the system “without specifying a limit of time” and said “the appointment of a female Archbishop of Canterbury would provide a particular challenge” in a church where a significant minority still do not accept female leadership.

The Bishop of Lichfield, the Right Rev Dr Michael Ipgrave, said the church was committed to “the flourishing of all within the church” including the “great majority” who support women priests and those who cannot do so, “without limit of time”.

Leave slave trader statues in place but be honest about their past

Only 15 per cent of priests back the removal of slave trader memorials and statues from church property, but two thirds would like to see information added alongside them to highlight their links to slavery.

Lord Boateng, Britain’s first black cabinet minister who now runs the church’s Racial Justice Commission, welcomed the results of the survey and said he hoped they would be “taken very seriously” as a sign that priests wanted to “confront the failings and sins of the past”.

Sonita Alleyne, the master of Jesus College, Cambridge, whose efforts to remove a memorial to Tobias Rustat from the college chapel were blocked by a church court after protests, warned, however, that simply adding extra information “may not be sufficient” to prevent some people feeling unwelcome in churches with such memorials.

The survey asked: “If there is a statue or memorial on church property dedicated to an individual who owned slaves or profited from the slave trade, what is the best course of action in your view?”

Of the 1,139 respondents, only 1.1 per cent, around 13 priests, said the memorials should be destroyed, while 13.9 per cent said they should be “removed from church property and moved to a museum or display space”, as was proposed in the case of Jesus College.

A memorial in a Dorchester church to a plantation owner that praised him for violently suppressing a slave rebellion was removed to a neighbouring museum this year.

A similarly small proportion (14.1 per cent) said such a memorial should be “left as it is” while a large majority, at 67.2 per cent, said such memorials “should be left in place, but with information added to explain the links to slavery”.

The Times understands there are a number of other contentious debates due to emerge in the coming months over what the church calls “contested heritage”.

Boateng said of the survey: “It demonstrates a recognition by the overwhelming majority of clergy of the seriousness of the need to confront the failings and sins of the past and that clearly is what clergy are committed to do.

“It is very helpful. It’s clearly an authoritative poll. It will be taken seriously by the commission and I hope it will be taken seriously by the Church of England.”

Alleyne said: “Contextualisation may not be sufficient to prevent memorials of this nature being a barrier to worship for people who are impacted by the ongoing legacies of transatlantic slavery and injustices — nor may it reflect the wishes of the community. The system needs reforming to ensure these issues are dealt with the care and sensitivity they deserve.”

A church spokeswoman said that it had issued “contested heritage guidance” for parishes and cathedrals to assess the “significance, impact and options” with their monuments and said: “There is no single approach that reflects the nuance and opportunities of local decision making.”

Many priests are at breaking point

Almost a third of working-age priests have “seriously considered” quitting in the past five years while more than 40 per cent feel “overworked or over-stretched”, with some citing an “abject” lack of support from bishops.

Campaigners calling for more resources to be spent on traditional parishes and on trying to return to a time when every church had its own dedicated priest said the results of the survey were “not good news” and show a “very worrying trend”, showing “how low morale is” among priests.

The poll found that two thirds of priests thought that efforts to stop the decline in attendance would fail, with only 10.1 per cent believing the decline would be halted and 10.5 per cent believing that congregations would grow again.

Some 26.1 per cent believed attendances will continue to fall at the same rate, 25.3 per cent said they would keep falling but at a slower rate, and 15.3 per cent thought the decline would accelerate.

Attendance at Sunday services fell to 690,000 in 2019, the last year of robust pre-pandemic figures, almost halving from 1.2 million in 1986.

In 2013, Lord Carey of Clifton, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, warned that the Church could be “one generation away from extinction” if it did not attract younger worshippers.

Almost a third of priests, at 31.9 per cent, agreed that “the Church of England could face extinction if decline continues”, although 56.6 per cent said that “even if decline continues, the Church of England will never go extinct”.

A total of 1,162 priests responded to a question about their workload, with 17.4 per cent warning that they felt “a little over-worked or over-stretched” and 10.9 per cent feeling very over-stretched.

However, when those aged over retirement age were excluded — such as priests over 70 who assist in lighter duties — a total of 40.5 per cent said they felt over-worked or over-stretched, with 24.2 per cent responding “a little” and 16.3 per cent responding “very”.

The days when each church had its own dedicated vicar or rector are long gone, leaving priests to cover wider areas and more churches within their parishes or benefices.

The survey reveals that 61.4 per cent of parish priests “manage or work across” more than one church, with 19 per cent working across five or more churches and 5 per cent working across eight or more.

The poll asked priests: “Has your workload or any other pressures of your role led you to seriously consider quitting the priesthood in the past five years?”

Among priests aged under 70, almost a third (32.7 per cent) said yes while 64 per cent said no.

Asked why, one priest cited an “abject lack of support” from senior clergy while another cited the “sheer relentless nature of the job coupled to no help whatsoever from those in authority over us”.

The poll found that 49.6 per cent thought bishops were doing a good job of leading the Church versus 42.5 per cent who thought they were doing a bad job.

The church recently scrapped a law stipulating that all churches must hold a service every Sunday, to reflect the fact that priests who run several churches cannot hold a service in every one each week.

Asked whether their own church would still be holding regular Sunday services in ten years’ time, 16.4 per cent said this was fairly or very unlikely, while 7 per cent said their church had already stopped.

Almost 40 per cent of priests think the church has got the balance “about right” between the money it spends on traditional parishes and on more modern “fresh expressions” of church in new styles and locations, but 37.7 per cent said they wanted to see more money spent on traditional parishes versus 18 per cent who want more spent on new forms of church.

Among priests of working age, 16.4 per cent said they were finding it fairly or very difficult to get by.

The Rev Marcus Walker, rector at Great St Bartholomew’s in London, runs the Save The Parish campaign group. He said: “It’s a hugely helpful [survey], particularly for the church authorities to realise quite how low morale is. I think they are so isolated from the realities of their clergy . . . It’s not good news. None of these responses are. They show a clergy where an awful lot of people are barely able properly to fulfil their jobs. It’s a very worrying trend.”

Dr Liz Graveling, who is leading research into the wellbeing of priests, said: “Our clergy provide unstinting spiritual, pastoral and practical support to their communities on a daily basis. We are seeking to listen to their concerns through research and through the adoption of a Covenant for Clergy Care and Well Being.”

The church said it had invested £3.6 billion in the mission and ministry of the church up to 2031.